In this issue:

January 2023

Reflections and Directions for 2023 – Priorities and Looking Forward

by Jann Dorman, Executive Director

The last few weeks have brought much needed rain and snow to California. Along with the drama and destruction, there have been numerous articles in the press about the amount of river water running out to the sea, and what should be done about it. My personal clipping service (my cognitively hyperactive, 97 year-old Jewish mother) has been providing me with regular updates on the subject. As I was reading a conservative blog this week, I came across this belief; it’s easy to store water, just dig a bigger hole and build higher walls. We may laugh (and cry) for the stupidity, destruction and injustice implied, but this belief captures a widely held view. Public awareness of the existential question of our time might be at an all-time high; How do we solve for flood and drought at the same time, with the same water? Public awareness of the answers remains very low. This existential question is at the core of what FOR works to accomplish, a California water future that is just and equitable, meets our urgent needs for adapting to climate change, actually works as planned, and most importantly is sustainable and resilient.

Before I share FOR’s 2023 priorities, and how they relate to our existential question, I want to step way back and talk about our overall strategy. You will be shocked to learn that you are not alone if you still don’t understand how FOR makes a difference, or what FOR actually does. I myself, spent most of this year struggling to understand. Friends of the River protects and restores California rivers by influencing public policy and inspiring citizen action. What does that actually mean?

Influencing Public Policy

FOR works to address the 5 drivers that determine the health of a river or watershed. These drivers have usually been articulated as threats in the past; hydropower dams, reservoirs, diversions, flood operations, litigation. We have fought against them for decades, and will continue to do so. However, a positive framing allows us to advocate for a solution: hydropower reform, saving & storing water, restoring flows, multi-benefit flood management, and legal protection.

At FOR, we track and examine the influence of these 5 factors across all the watersheds in California. Within that array, we prioritize the policy objectives. The decisions to build a dam, decommission a dam, or operate a dam and reservoir in a way that kills fish or supports fish (for example) are all driven by policy and regulation. Decisions about how much water goes to the environment, how much to people, how much to agriculture, and the impact on our rivers, are driven by policy and regulation. FOR is a stakeholder and participant on your behalf in the public decision-making process to shape these policies and regulations.

It’s also important to acknowledge the importance of the organizations engaged in actual on-the-ground land and watershed restoration. However, while FOR will advocate for the important restoration project approvals, we do not now actively engage in restoration projects. To see the details for FORs anticipated 2023 policy priorities, please click this link.

Inspiring Citizen Action

At FOR, we believe that healthy rivers are critical to a climate resilient water future for California. To achieve that water future, we seek and support solutions that are: just and equitable, timely, effective, and resilient (our values). The California I value is laced with healthy rivers. I think most (if not all) of you share these values. We would like many more Californians to share these values, and we would like to better connect with those that already do. At the end of the day, our collective success in creating our water future will be dependent upon broad-based sharing of these values.

To quote Marshal Ganz, (of whom I am a devotee) “Movements have narratives. They tell stories, because they are not just about rearranging economics and politics. They also rearrange meaning. And they’re not just about redistributing the goods. They’re about figuring out what is good.” However, public narrative alone is not sufficient. We also need more leaders who can organize to build purposeful, collective action. To quote Marshall Ganz again; “Leadership is taking responsibility for enabling others to achieve shared purpose under conditions of uncertainty.” Leadership development is a force multiplier. FOR has long engaged in building leadership capacity for river advocacy, and is continuing to do so with renewed urgency. This will be a huge area of focus in 2023.

We have a great deal to do to rise to meet the urgent challenges of today, and rebuild from the past challenges of the pandemic and fires. To see more on FORs work to inspire action for 2023, please click this link. For those of you who would like to learn more about the social movement theory of Marshall Ganz, click here.

We can now come back to FOR’s overall strategy and operating plan for 2023. To see how the pieces fit together, please click here. I will venture to say at the end of all this, there is nothing new here. My sincere wish is to simplify and clarify what have been doing for decades. For those of you who have made it through this exercise, we welcome your thoughts and input. I understand not everyone enjoys reading and writing about the obvious as much as I do. However, we are all part of the solution. We need to be aligned on what we are trying to do and how we will do it. And to be able to tell our shared story in ways that bring more power to our efforts.

Currents: Victories and Threats

Ron Stork, Senior Policy Advocate

Wild & Scenic River proposals wrap-up

Last month I speculated that the California wild & scenic river designation package and the Oregon Smith River National Recreation Area addition / wild & scenic river designation would fail to achieve final passage in this past Congress (117th), just as they had failed in the preceding Congress (116th) (and briefly introduced and died in the Congress before that (115th)).

The 117th Congress is no more. These important bills to Oregon and California lawmakers failed to find a must-pass omnibus bill in which they could be included, and they were not passed as stand-alone bills. So once again, river advocates will be starting over, but this time in the 118th Congress and on the turbulent and potentially hostile waters of the House of Representatives under its new Speaker of the House, Representative Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield).

The California package contained the proposed San Gabriel Mountains Foothills and Rivers Protection Act (Rep Judy Chu), Northwest California Wilderness, Recreation, and Working Forests Act (Rep. Jared Huffman), and Central Coast Heritage Protection Act (Rep. Salud Carbajal). The bills were supported by both of California’s U.S. senators, who offered a Senate companion.

The North Fork of the Smith River is in Oregon. The Oregon package proposed to add to the adjacent national recreation area and state and national wild & scenic river in California — in effect providing better protection to one of the most pristine river and watersheds in the state of California. (Oregonians explain the Smith’s pristine status because the Smith River is practically in Oregon — and they have a piece of the Smith River too.) Like the California package, the Smith River bill was supported by the Oregon U.S. Senate delegation, who offered the bill.

We will let you know when and if the bills are reintroduced in the 118th Congress, something that at this writing seems likely.

Winter and the rains return — a Sacramento Valley perspective

It’s certainly been a wet winter so far, almost wearying. If this trend stays for the next few months, it may be another 1982-83 winter, a year of generous rainfall and runoff, but not huge rainfloods. Nevertheless, that was a year where we looked forward to the end of California’s rainy season and appreciated the words of the Song of Solomon, “for behold, the winter is past; the rain is over and gone. The flowers appear on the earth, the time of singing has come” (ESV). Yes, 1983 was a great wildflower year — and not too bad for river critters either. Maybe 2023 will be as well.

This winter, predictably, has also been a time where the grumpy among us begrudge enjoying nature’s bounty, looking instead to hoarding it behind concrete even more than California’s 1,200+ existing dams already accomplish that task — at some considerable sacrifice to our rivers.

The grumps speak of megastorms with massive floods. They dredge up dark memories of the storied California 1862 flood. A prominent syndicated columnist echoed that theme.

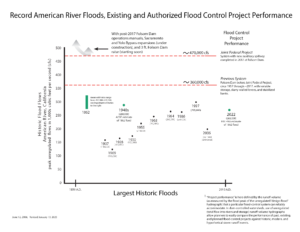

Dan Walters is an erudite guy, but perhaps some deeper history and science is called for. Determining the runoff of the 1862 flood cannot be easily established with precision. And during the gold rush era, without the levees of today, it didn’t take that much water to flood up the huge sediment deposition basins that line both sides of the Sacramento River — basins that carried (and still carry) the large majority of the Sacramento River safely to the San Francisco Bay (think Yolo Bypass for example). Here in the Sacramento Valley, though, the modern flood conveyance and reservoir system was successfully designed with the 1862 flood in mind.

Last year, the California Extreme Precipitation Symposium received a presentation from a team of hydrologists who took up a modern reconstruction of the 1862 flood flows on the American River. The historic gorge near Folsom was reconstructed from photographs and careful records, high water marks were reassessed, and the flow of the 1862 event was modeled using contemporary software. The resulting peak flow estimate (“discharge” in hydrology-speak) was slightly lower than the estimate by the 1940s-era slide-rule-using engineers from the U.S. Army Corps.

The 1940s discharge estimate was the preliminary basis for the Folsom Dam design. Interestingly, even back in the day, the Corps designers were conservative in project design. The Corps stated in a 1974 comment on the Auburn-Folsom South Unit FEIS:

“In the design of Folsom Reservoir, the Corps of Engineers recognized the need to provide protection against a very large winter rain flood. The flood of January 1862 was thought to be the largest experienced flood for which estimates could be made, and those estimates were initially considered… for the Folsom flood control design operation plan. Objections [were] raised… based on flood control experience throughout the United States [which] resulted in discarding the estimated 1862 flood hydrograph and preparing a revision of the design flood to assure that a higher… degree of protection would be provided by the flood control operation…”

Since Folsom Dam’s original construction, a lot of expensive work has been and is still slated to be done to the dam and downstream conveyance capacity. New operating rules have been completed to take advantage of modern weather forecasting. Some similar plans will be completed for the New Bullards Bar Dam on the Yuba River. The state’s Oroville Dam is not currently slated for improvements (although FERC can and should order some), but a modernized flood manual is in the works. There’s lots of details about the Valley, and much can be found in the 2022 Central Valley Flood Protection Plan (CVFPP) and related documents.

In summary, while much more work in the Valley is contemplated by the state’s CVFPP and some floodplain management decisions await, more “flood-control” dams need not be in the Sacramento Valley’s future. Whether the water barons succeed in getting more dams constructed to feed California’s water supply machinery is another matter. However, Friends of the River will work to make sure that flood control is not the excuse for more concrete in our waterways.

Winter and the rains return — a wider perspective on the 1862 flood

The expected flood future of other parts of California may not be so sanguine.

A little to the south of the Sacramento Valley, the warmer and juicier rains of the future will fall on the typically snow-clad high-elevation Sierran mountains east of the San Joaquin Valley. Today’s dramatically reduced river corridors of the San Joaquin Valley mean that the giant dams there may be unable to maintain their flood space reservations in the face of weeks and months of high inflows like those experienced in 1862. This is because there is not enough room for the river, downstream of the dams, to safely move high flows. For example, in recent high-water years, the modern Don Pedro and Friant Dams have filled and spilled. However, there are options. For example, in 2017, modified operations at Don Pedro avoided downstream flooding and filling and spilling by experimentally increasing releases beyond their designated floodway capacity.

Nevertheless, in the absence of major improvements to downstream floodways, filling and spilling is inevitable. Eventually, in water-rich years like 1862, one additional rainflood (or a large and extended snowmelt season) can put this valley’s dams into inflow-equals-outflow conditions. Big water not experienced below many of these dams for more than a half a century would return. The San Joaquin Valley lowlands will flood, likely including many Delta cities. Facing that arithmetic will not be pleasant, but in the end, resistance will be futile, sooner or later, and problem-solving will have to return.

The San Joaquin Valley needs more room for its great rivers and recognition that some nearby lands will be pond water from time to time. In exchange, floodflows can be better managed, both in frequency and magnitude, vulnerable infrastructure floodproofed or relocated, and the Valley’s prosperity made more resilient.

Facing the consequences of large flood years such as 1862, or modern climate-change reconstructions, should be considered with some humility. The design assumptions for the modern California built environment, from its Southern California alluvial floodplains, its coastal plains, its Great Central Valley, and its rural hinterlands should be revisited. And prominent among the assumptions for responding to and rebuilding the state’s future must be leaving more room for nature to be safely nature — along with (1) where and how we build and (2) manage and recover from flood emergencies.

Whether we are up to that challenge, will be the work of today’s and the future’s citizens. And the sooner we recognize that challenge, the better the outcome of our work.

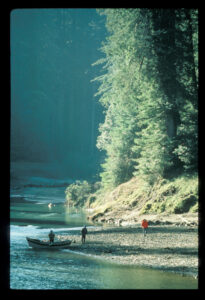

The Cosumnes River in the national news

The Cosumnes River in south Sacramento County originates in mid-elevations in the Sierra Nevada, sandwiched between the South Fork of the American River to the north and the Mokelumne River to the south. Unlike any other Sierran River, it flows essentially undammed into the San Francisco Bay-Delta.

It also floods. Big time.

Below the snowline during large rainfloods, this watershed has flooded up this year dramatically enough to make the national news (the east-coast national press always enjoys a good west-coast disaster story).

Here, the levees are “sugar” levees, levees so close to the river that they have no hope of surviving the high water that arises from time to time in the Cosumnes.

The County historically has been firm about preventing some levees from being reinforced so that they don’t act as dams and enlarge the river’s floodplain unnaturally and unpredictably. Here, it is best that levees don’t mount heroic resistance to mother nature. “Sugar” they must remain, reliable enough to protect farm fields in the small floods, but not so in the larger ones.

Of course, that means man’s infrastructure that ventures onto the Cosumnes’ floodplain should best plan for weathering or avoiding the floods. Many of the houses and ranch buildings there are elevated or otherwise prepared for flooding. More probably should be.

The County roads in the Cosumnes Basin flood during flood times. Inconvenient, but that’s the way it was designed. State Highway 99 flooded up this year too. CalTrans did not close it in time. Some motorists were stranded. Tragically, some died. CalTrans promises that it will be ready to close the route in time in the future. According to press accounts, it also recognizes that the roadbed should be raised someday, although there are no plans to do so at present. CalTrans, too, would need to make sure that a future Highway 99 does not block flows and create a flooding nuisance to its neighbors. There are ways to do this, although it takes some money.

Adopting another important perspective, the Cosumnes River floodplain contains an extensive Nature Conservancy Preserve and government wildlife refuge. The nearby agriculture lands and the Preserve/refuge wildlife are one of the glories of Sacramento County. The floods there should also prevent housing sprawl. Not every part of California should sprout cities. The Sacramento Bee echoed this perspective in a recent article about flooding on the Cosumnes.

These flood-prone lands are not wasted — or wastelands. Instead, they show how communities can live with and enjoy the natural and less civilization-touched world around them. Let’s hope that continues. Many of us will need to work to keep it that way.

Someone should let the national press know about that story too.

Reflections on living in a flat place

I haven’t always lived on a flat place. I grew up on an alluvial fan of the San Gabriel Mountains in Southern California.

The evidence of high-velocity water transport was everywhere: the sands of the garden were full of rounded river rocks, the older houses in town had foundations of large rounded field stones, and the major north-south streets were designed to convey the occasional torrents coming off the mountains (and to terrify small children walking to school who could be swept away as they tried to cross those streets).

When I moved to the Central Valley, I settled in Merced. The ground in and around it was flat, good bicycling country. The land was also cut with a few leveed streams that received water from the foothills and toehills of the Sierra Nevada to the east.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had constructed four or so little flood control dams on the mostly ephemeral nearby creeks in the 1940s and 50s. The creeks had been leveed up and dredged in and around town by the Merced Irrigation District, the County, the City, and the Corps for decades — and more would come later. The District used some of them as irrigation canals. The creeks, as was the custom of the time, were straightjacketed by levees, maximizing the land “reclaimed” and minimizing the potential size of the waterways.

In 1950, Bear Creek, the city’s “river that runs through it,” had overflowed and inundated about thirty blocks in the east side of town. Although many homes there had been built well above the streets, many other homes experienced damage. The 1950 flood had been preceded by floods in 1911 and 1935, and followed by floods in 1955. (More on recent Bear Creek flooding).

By the time that I moved to town in 1975 (and rented on the second floors), the city was expanding and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) had mapped most of it into AE zones (zones that required the purchase of flood insurance and displayed the expected depth of flooding and required new construction to be elevated). Some of the areas slated for commercial development were just A zones (zones that did not map flood depths and thus had no building requirements for new construction). The latter circumstance would result in some ill-considered major building in the town’s deepest floodplains before the AE zone mapping could be completed.

I purchased a 1920s-era home in 1982 in the one-foot deep zone and figured that the house was only an inch or two short of that. If I had the money back then, I would have just raised the house a foot or two and slept a little better at night during heavy rains.

The FEMA program had only begun in 1968, so much of the housing stock in Merced was pre-FIRM (FEMA-speak for flood insurance rate maps delineating and characterizing Merced’s floodplains). FEMA’s program hoped and still hopes that the housing stock gets elevated over time to prevent and reduce flood damages and community trauma and loss of life. (Structures that experience 50% damage are required to be relocated or elevated.)

The program has not been too successful. Instead, many communities rely on the Corps for levee patch ups to keep them out of the AE zones — while the town still remains vulnerable to ground-squirrel digging holes in their levees or higher water than FEMA’s estimated “regulatory flood.” Others just stay in the AE zone. In neither case are the properties floodproofed.

I moved away from Merced in 1983 and lost track of the day-to-day details of the city. The Black Rascal Creek levees broke in, I think, 2006, flooding some of the newer areas in the northern and western parts of town, much of which experienced five or so feet of flooding, just like FEMA maps said they would.

Today, the large majority of the City of Merced is in the FEMA AE zone (property owners paying off house loans have to purchase flood insurance). Half the population are renters, nearly always without flood insurance. At this writing, much of Merced had been teetering on the edge of flooding and east Merced along Highway 59, the deeper part of town, had experienced significant flooding from Bear Creek overtopping its levee.

Planada, its neighbor to the east, has just flooded from Miles Creek and the town evacuated. Nearly all of Planada’s residences are renters, and much of the housing stock there is pre-FIRM, meaning the properties there are not floodproofed and the financial recovery from floods is a huge hurdle since flood insurance is not required from renters. (Article on recent Planada flooding).

Making cities and towns in the flat places in the California Central Valley less vulnerable to creek flooding is not something that many places have a realistic game plan to achieve. More importantly, most will not achieve this within the next five years, the expected result of landmark legislation passed in California in 2007 — legislation that Friends of the River helped shape.

I think that most non-conforming communities are hoping that the legislature will extend the deadlines for years to decades.

This year’s generous rainfall will be reminding city councils, boards of supervisors, and the legislature of the important work of mending the historic settlement patterns and building practices of the past — and hopefully mending the creeks and rivers at the same time.

Stay tuned. Better yet, get involved.

Remembering Bill Jennings, a Delta hero

Keiko Mertz, Policy Director

This December, the California water world abruptly lost Bill Jennings, esteemed activist for the Delta, California rivers, and their inhabitants. Bill dedicated more than half of his life to fighting for healthy ecosystems and just water management.

Originally from Kentucky, in his younger years Bill developed passions for civil causes, tobacco, and fly fishing. By the 1980’s he found himself in Stockton, California, where he opened the Delta Angler – a shop reflecting his affinities for both fly fishing and tobacco. Following a massive fish kill on the Mokelumne, Bill also developed an insatiable appetite for using his voice and cleverness to protect the environment. It was during the Mokelumne era that FOR became acquainted with Bill, crossing paths with him frequently. Bill’s work on saving the Mokelumne was critical to the efforts.

Bill eventually went on to focus his advocacy on the Delta, working to protect it and its tributary watersheds from exploitation by the proposed Peripheral Canal (an ancestor of the Delta Tunnel).

Throughout his 40+ year career as an environmentalist, Bill co-founded the Committee to Save the Mokelumne, worked as the Deltakeeper (1995-2005), and worked as Executive Director of the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance (2005-2022). He also served as a board member for both the California Water Impact Network and Restore the Delta. Bill was a decorated environmentalist, earning recognition from the U.S. Congress, the California State Legislature, San Joaquin County, the CA Dept. of Fish and Wildlife, the American Fisheries Society, and most recently, he was inducted into California Outdoors Hall of Fame.

He will be sorely missed.

To read more about Bill and his legacy:

January Wild and Scenic River Anniversaries

by Ron Stork, Senior Policy Advocate

January 20, 1981: In the last River Advocate “Wild & Scenic River Anniversaries” section, I told some of the tales surrounding the creation of the California Wild & Scenic Rivers Act some 50 years ago. The California system protected the Smith River and all of its tributaries; the Klamath River and its major tributaries, including the Scott, Salmon, and Trinity Rivers; the Eel River and its major tributaries, including its tributary the Van Duzen River; and segments of the American River.

But more adventures would lie ahead for these rivers and for California’s wild & scenic river system.

Of course, while lovers of the state’s rivers celebrated the system’s creation in 1972, the state’s water industry continued to plan for the next link to access all these north state rivers — the Peripheral Canal, which would transport water around the San Joaquin and Sacramento River Delta. Governor Jerry Brown was committed to taking this next step in Governor Pat Brown’s grand (or certainly consequential) creation, the State Water Project (SWP). And while the water agencies and their beneficiaries worked to advance such concrete projects, the river community was deeply committed to preserving and protecting Governor Ronald Reagan’s grand creation, the California wild & scenic river system.

Legislative maneuverings (SB-200, Prop 8, and Prop 9):

By 1980, the Capitol was trying to fashion a way through these conflicting visions. The Capitol felt that the big canal needed legislative authorization, so SB-200 (Ruben Ayala, D-Chino) did that trick. The bill had provisions for many of the interests in the Capitol. In addition to authorizing the Peripheral Canal, it authorized two large proposed reservoirs, the Glenn-Reservoir/River (and the Colusa Reservoir if the Glenn project failed) and the Sites dam project (all reservoirs on the west side of the Sacramento Valley). Sites was to be a federal project. And, to bring Sacramento River water to agriculture on the east-side of the San Joaquin River (which, even then, was depleting groundwater), the big Mid-Valley Canal was authorized. It would draw Delta water from the Peripheral (proposed) and Delta-Mendota Canals to moisten the verdant farmlands watered from the slopes of the western Sierra Nevada mountains.

To assuage the environmentalists, SB-200 spoke of water quality objectives. Other assurances were offered too: the legislature put Proposition 8 on the ballot. Prop 8 required that out-of-basin storage or diversions from California’s wild & scenic rivers would have to be approved by state voters or a two-thirds vote of the legislature — useful assurances, but Prop 8’s effect was contingent on the passage of SB-200. With mixed constituencies in favor, Prop 8 passed in the 1980 November general election by nearly a 54% to 46% margin of victory.

However, the hoped-for truce in the California water wars did not materialize. SB-200 was challenged by a mixed coalition including select environmentalists and Tulare Basin agricultural interests. These environmentalists objected over some of the SB-200 package project authorizations. The Tulare Basin folks wanted “their” north coast rivers back (and not to have to pay their part in the bill for the Peripheral Canal). Together this unlikely team managed to qualify and win a statewide referendum. SB-200 was defeated by Proposition 9 in the 1982 general election — with the wild & scenic river assurances of Proposition 8 as collateral damage.

The tale of a governor and the Secretary of the Interior:

But back in 1980, no one could confidently predict the events in 1982. Were there other assurances for the river folks to prop up the, perhaps shaky, guarantees offered by the state wild & scenic rivers system? After all, the “permanent” guarantees of the system had been created by a 50% vote in the state’s legislature and a governor’s signature. It wouldn’t take much for the vote to go the other way. Were there other ways of making the system more resilient?

Yep, this could be accomplished through the back door of the National Wild & Scenic Rivers Act, which contained a provision that allowed the Secretary of the Interior to add state wild & scenic rivers into the national wild & scenic rivers system at the request of a state’s governor. On July 18, 1980, Jerry Brown did just that.

Sensing that federal designation just might put the north coast rivers (and perhaps the American River, too) out of reach for their plans to tap these rivers for south state and Central Valley irrigators, the reaction was immediate and strong. Lawsuits were filed in state and federal courts attempting to stop Secretary of the Interior Cecil Andrus from acting on Governor Brown’s request. The state’s powerful water industry, long accustomed to slavish service from Congressional appropriators, strove valiantly to place appropriations riders to prevent Andrus from taking action.

In the meantime, and further demonstrating the perils to California’s state wild & scenic rivers system, in 1980 the California state senate voted 23–6 to gut important provisions of the Act (although this measure did not win final passage). Clearly the state senate had changed its sentiment on rivers from when it passed the California Wild & Scenic Rivers Act in 1972, merely 8 years before this bid to gut the Act.

While political and courtroom dramas played out, Interior’s Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service (HCRS), an agency later abolished by Ronald Reagan’s Interior Secretary James Watt, had the job of preparing the environmental impact statement (EIS). Jim Huddlestun, the HCRS Rivers Programs Coordinator, led the federal team. John Cherry, the HCRS regional director and his assistant director, Brian O’Neill, would eventually sign the EIS. John Haubert helped at the Washington DC end.

Interior’s efforts were aided by the huge support provided by staff from Brown’s Department of Water Resources (DWR). The EIS teams worked at a fast pace. A draft EIS was out on September 19, 1980, and a final EIS finished by December 9 and posted in the Federal Register by December 16/17. Secretary Andrus, the Secretary for the Jimmy Carter Administration, then had to wait 30 days before signing the document. Inauguration Day for the incoming President Reagan was on January 20, 1981. It was down to the wire.

In the meantime, the usual end-of-session rush to fund the federal government was occurring. The appropriations bills were late. The Congress was in a “lame duck” session to accomplish last-minute goals before the Republicans assumed control of the Senate. The appropriation bills or the continuing resolutions were shaping up to be full of riders of various sorts. Senator James McClure (R-Idaho), the incoming chair of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, with the support of Senator S.I. Hayakawa (R-California), offered the rider to prevent Andrus from taking action on Governor Brown’s request. Senate Democrats, though, understood that incoming Senate Leader Bob Dole (R-Kansas) wanted a clean bill — that meant no riders (including the publicly unpopular rider to give the Congress a pay raise). Representative George Miller (D-Martinez) worked to stop the anti-Andrus rider in the House. On December 16, 1980, when all was said and done, to the considerable astonishment of California’s water agencies, no Congressional rider prevented Andrus from accepting the designation.

But things were not going so well in the courts. The superior court in Sacramento County had agreed with the water industry plaintiffs that the state did not really have the power to manage its National Wild & Scenic Rivers Act responsibilities. Fortunately, the Sacramento court also ruled that it did not have the power to stop Brown from making the request to Secretary Andrus.

But there were still courts that could stop Andrus. The federal district courts in Portland and San Jose were not happy with some of the procedural details of the EIS chronology. By January 15, 1981, they had placed preliminary injunction that prevented Secretary Andrus from acting on Governor Brown’s request until the choice would be made by incoming Secretary of the Interior James Gais Watt. Watt was not much of a friend of wild & scenic river system expansions.

California requested an emergency reversal of the preliminary injunctions from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. But how would they respond, and would it be in time?

A family member of the founder of the California Committee of 2 million, one of the groups that had spearheaded the creation of the California Wild & Scenic Rivers Act, visited Secretary Andrus on his last day in office. By then, Secretary Andrus had decided to ignore the White House Chief of Staff’s order for all the cabinet secretaries to hand in their resignations by close of business on January 19 as part of the orderly transfer of power to the incoming President Administration. Andrus had promised to serve Carter for Carter’s entire administration. The requested resignation could wait.

At that visit, the question was asked, what would Andrus do in the unlikely chance that the injunctions were lifted? Andrus pointed to a little desk in his office where the transfer document had been prepared for his signature. The implication was apparent.

By that evening in Washington DC, at 3:30 p.m. Pacific Time, the Ninth Circuit had dissolved the injunctions. While the water agencies searched for then-Associate-Supreme-Court-Justice William Rehnquist to stay the Ninth Circuit’s injunction, California was trying to contact Secretary Andrus. Luck was with California. Andrus was at a White House event with President Carter and his departed cabinet secretaries.

The White House Switchboard found Secretary Andrus. Andrus, now the sole remaining Carter cabinet secretary, walked back to the now well-after-hours Department of the Interior building and signed the document — formally witnessed by a federal janitor.

Two days later, Department of the Interior staff found the signed document. Most of California’s original wild & scenic rivers (the federal designations of the Smith River a few other details were different) were now part of the national wild & scenic rivers system. California’s powerful water agencies had narrowly lost the battle in the legislature, the Congress, and the courts — at least for the purposes of our wild & scenic river anniversary date in history, January 20, 1981.

The fight to save the designations would continue, but those are stories for another day.

For a somewhat deeper dive into the history of the state designations, Friends of the River’s ever-lengthening California wild & scenic rivers memo is the place to go.

River Advocate Back Issues

September 2022

September 2022

Back Issues of Headwaters Newsletter