Act Locally. Connect Globally.

by Betsy Reifsnider

Friends of the River proudly calls itself the voice for California’s rivers. But sometimes our voice merges with river voices around the world.

As Executive Director from 1996-2004, a few memories stay with me. For instance, when water engineers from Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Oman came to Sacramento, they sat around our conference table, asking why Friends of the River would stand in the way of new hydropower facilities. After our hydro expert Maureen Rose gave a passionate explanation over tea and cookies, the Oman engineer admitted, “My dad always told me that free-flowing rivers were a gift. I never understood that until now.”

I remember a government delegation from the People’s Republic of China looking into grassroots organizing. To prepare for the meeting I called International Rivers in Oakland, an earlier stop on the delegation’s itinerary. “Don’t tell them anything!” came the reply. The real reason for the visit was to learn how to counter efforts by local activists seeking to protect China’s rivers.

I remember a government delegation from the People’s Republic of China looking into grassroots organizing. To prepare for the meeting I called International Rivers in Oakland, an earlier stop on the delegation’s itinerary. “Don’t tell them anything!” came the reply. The real reason for the visit was to learn how to counter efforts by local activists seeking to protect China’s rivers.

Sometimes I was the one traveling to spread our message. In 1997, I joined a U.S. Interior Department delegation to South Africa. The goal was to advise South Africans on effective water efficiency measures; instead we were inspired by South Africa’s “Blue Revolution” as newly elected President Nelson Mandela transformed the country. Their Minister for Water and Forestry explained, “Until now, water conservation hasn’t been important. It’s not as sexy as building dams. Now it is time to move toward the ‘feminization of water management’–a more people-oriented, systematic, gentler approach.”

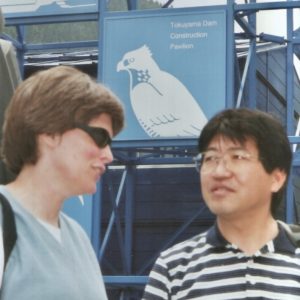

But perhaps the most poignant river voice came from Japan. In 2001, the Japan Entropy Society contacted us. Aware of FOR’s epic battle to stop the Auburn Dam, they asked if we could send someone to help them stop their Tokuyama Dam. My husband Bob and I flew to Japan where we spoke to classes at Nagoya University. The Entropy Society then drove us by van to the heavily-forested mountains of central Japan to see the largest dam project in the country, named for the soon-to-be-flooded Tokuyama village, inhabited as far back as 14,000 BCE.

But perhaps the most poignant river voice came from Japan. In 2001, the Japan Entropy Society contacted us. Aware of FOR’s epic battle to stop the Auburn Dam, they asked if we could send someone to help them stop their Tokuyama Dam. My husband Bob and I flew to Japan where we spoke to classes at Nagoya University. The Entropy Society then drove us by van to the heavily-forested mountains of central Japan to see the largest dam project in the country, named for the soon-to-be-flooded Tokuyama village, inhabited as far back as 14,000 BCE.

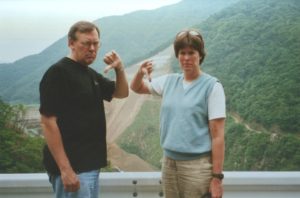

Construction of the dam stopped in 1957 because water demand had not increased as expected. Just as the reasons for building California’s Auburn Dam shifted over time, by the late 1990s the Tokuyama Dam was declared a multi-purpose project for hydropower and flood control. Dam construction as an economic stimulus became national policy; opposition was silenced.

In 2001 the Tokuyama Dam was virtually complete. Soon the floodgates would close and the waters would rise. Nothing could stop it; Japan’s river advocates had lost this fight, just as Friends of the River had lost our struggle to save the Stanislaus River. Our tour guide, an elderly woman from the village, sighed, “It is useless for an ant to resist a big river. Instead of doing such a stupid thing, I decided to save as many things as possible.” In that spirit and after a grassroots campaign by villagers and a fisherman’s union in southern Japan, the country began to remove its first dam in 2012, with others on the way.

In 2001 the Tokuyama Dam was virtually complete. Soon the floodgates would close and the waters would rise. Nothing could stop it; Japan’s river advocates had lost this fight, just as Friends of the River had lost our struggle to save the Stanislaus River. Our tour guide, an elderly woman from the village, sighed, “It is useless for an ant to resist a big river. Instead of doing such a stupid thing, I decided to save as many things as possible.” In that spirit and after a grassroots campaign by villagers and a fisherman’s union in southern Japan, the country began to remove its first dam in 2012, with others on the way.